Many organisations act as inhibitors of innovation.

Rules and protocols are put in place, often for very good reasons, that preserve the status quo. Over time, organisations develop a set of social norms – ‘the way we do things around here’ – that can quell any creativity or dissent.

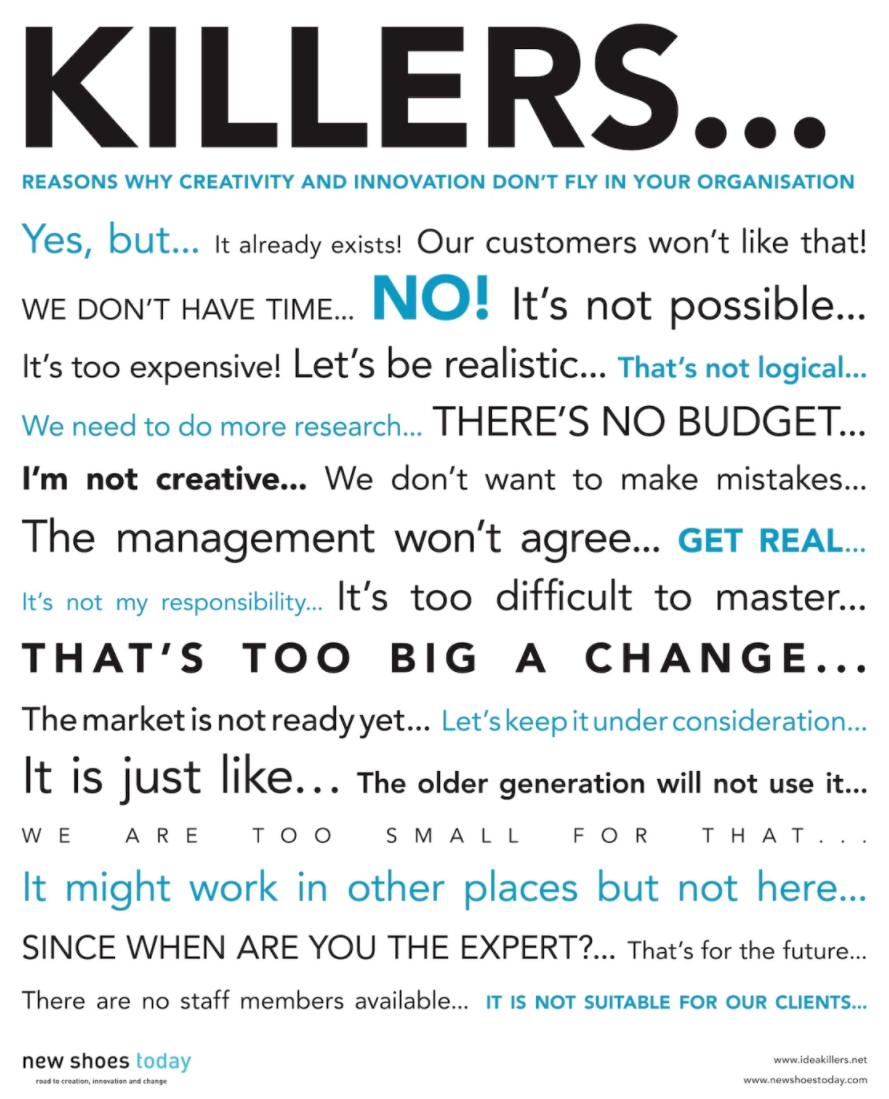

Organisations can quickly develop an autonomic immune response that kills ideas – without any conscious effort. This immune system builds up easily and quickly spreads, but is far harder to dismantle.

One of the ways you can begin to repel these idea antibodies is , as Chris Bolton has outlined, to deploy a sort of ‘immunosuppressant agent’. This may simply be strong leadership saying ‘all new ideas are welcome’.

In my last post I shared how Bromford are attempting to democratise innovation by asking the 50 most senior leaders in the organisation to develop their skills by daring to disagree with each other and becoming more receptive and open to challenge.

Working with my LD50 colleagues we established a Developing Ideas Group where we encourage colleague to submit ideas that save us money or improve customer or colleague experience. We are trying to distinguish between simple ‘ideas’ that lend themselves to a ‘crack on and try it approach’ with a complete acceptance of failure, and the more complex/higher risk problems.

The more complex problems are presented through a colleague pitch.

Asking colleagues to pitch ideas is a high risk venture. There is a glorification of the pitch in business today. Startup events and innovation challenges are popping up everywhere. Hacks are common, with 24 hour business creation marathons where strangers connect and form solutions together. Every such event revolves around the pitch and the skills and strategies required for an effective pitch.

Asking people to pitch ideas can fail as it forces people to rush to solutions. Which hastily assembled pitch should we bet on? The answer should often be: none of the above.

Pitching ideas is often just innovation theatre. Too many Executives fancy themselves as budding Dragon’s Den investors – waiting to show their business acumen by outwitting the person pitching. Many years ago I took part in a innovation challenge that followed the Den format so closely you could almost guess which Dragon the Executives were pretending to be. It was a dispiriting experience, with colleagues emerging either crushed or with a lot more work to do – often with no more resources.

At Bromford we are trying to do something slightly different – asking colleagues to pitch really great problems rather than firm proposals.

We’ve been coaching some of the Leadership team using nemawashi principles – so the rule of the pitch is that you can’t shoot any idea down – or even criticise it – you can only ask questions.

As I have previously written Nemawashi is a Japanese phrase translating into ”an informal process of quietly laying the foundation for some proposed change or project, by talking to the people concerned, gathering support and feedback, and so forth.” In Nemawashi the potential solution is prepared in very draft form but this time we check in with any colleague with a significant organisational position, not just bosses, to build consensus.

As David O’Gorman has written the nemawashi–ringi process is grounded in the need to maintain harmony within the organisation while at the same time make sound decisions. An advantage of the nemawashi–ringi process is that once a proposal is approved it can be rapidly implemented because all the relevant parties are on board. This is in contrast to Western processes, which can encounter obstacles during implementation, even from parts of their own organisation.

Ideas are easy to kill – problems aren’t

Simply unleashing ideas just isn’t enough. They are too vulnerable, too easy to kill off. If we anchor ideas in truly great problems you’ll find that colleagues build on the initial idea rather than attempt to destroy it.

A problem shared really IS a problem halved. Most problems do not fit neatly into one team or function and require input from a variety of perspectives. That’s why attempting to solve them in operational meetings with the usual suspects is a waste of time. By harnessing the creativity, expertise, and ingenuity of the wider organisation as willing volunteers, we can solve problems in a more inclusive, efficient, and effective way.

And here’s the point: people don’t resist an idea they have helped define.

So don’t criticise ideas. Just learn to ask better questions.