Written By: Gigi Shaw What three major changes have happened to commentary: and what are the impacts of these on individuals, organisations, and industries? Compared to the traditional media of old, three things distinguish the financial services commentaryof today: speed, simplicity, and emotion. And with good reason; audience expectations of real-time coverage mean less time to research and verify, in addition to shorter news cycles. Technology means wider, faster reach of commentary – as well as an almost equal platform for any commentator, expert or amateur. It also means higher audience/public engagement, which in turn exaggerates response. Fierce competition for web traffic increases the pressure towards sensationalism and away from balanced reporting, while shrinking resources mean wider beats and more demands on reporters’ time – decreasing their specialisation or subject expertise.

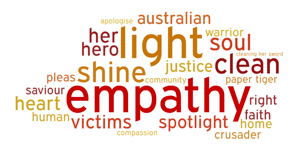

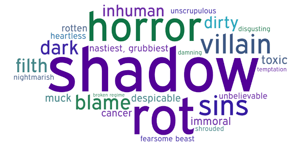

The Royal Commission lawyers used many of the same tactics for the same reasons – often driving and framing the resulting coverage. Lawyers, like the best politicians, know how to use the power of story. In fact, the ‘baby-faced assassin’ QC Michael Hodge wrote Clinton: The Musical , years before his Commission performance. Self-interested as it sounds, our analysis also showed a difference in reputational outcomes between those brands who ‘left it to the lawyers’ to run all aspects of their performance, and those who applied more specialist narrative expertise (such as PR advice). But the use of familiar narrative patterns also meant that for those involved it was a zero-sum game – you were a hero warrior like Rowena Orr, or you were a villain; you were either creeping around in the shadows or you were shining the torch. There were no grey areas left on the map. This, in turn, predetermined the ending for many of the characters – because we all know what happens to the wolf after he bullies the pigs, or to the evil, greedy banker who steals from the poor, the weak, and the dead.

The Royal Commission lawyers used many of the same tactics for the same reasons – often driving and framing the resulting coverage. Lawyers, like the best politicians, know how to use the power of story. In fact, the ‘baby-faced assassin’ QC Michael Hodge wrote Clinton: The Musical , years before his Commission performance. Self-interested as it sounds, our analysis also showed a difference in reputational outcomes between those brands who ‘left it to the lawyers’ to run all aspects of their performance, and those who applied more specialist narrative expertise (such as PR advice). But the use of familiar narrative patterns also meant that for those involved it was a zero-sum game – you were a hero warrior like Rowena Orr, or you were a villain; you were either creeping around in the shadows or you were shining the torch. There were no grey areas left on the map. This, in turn, predetermined the ending for many of the characters – because we all know what happens to the wolf after he bullies the pigs, or to the evil, greedy banker who steals from the poor, the weak, and the dead.

The Banking and Financial Services Royal Commission: a case study in new media

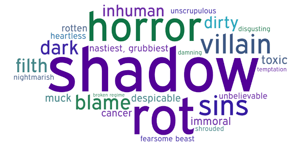

We analysed commentary around the Royal Banking Commission closely last year ( you can read our insights here ), and end to end it was a masterclass in the “new normal” when it comes to commentary. We saw interesting patterns that demonstrate, albeit in a more exaggerated way, the changes we’ve seen in the wider environment. Commentary was:1. Immediate - Commentators were often covering proceedings minute-by-minute, and then going away and filing a story, or developing a take, mere hours after hearings stopped for the day. 2. Simpler - Commentators dealt, not just literally in black and white, but very much in almost primitive blunt outlines. Reductiveness was understandable: the hearings were incredibly complex in parts. Many in the institutions themselves didn’t understand the whole picture of their businesses, so how could any non-specialist outsider covering proceedings – or their audience? But in addition to the complexity of the subject, the need to publish in real-time or soon after demanded simplification. 3. Emotive - The complexity of the story – and the dryness of the subject matter when it came to the details of policy, process, terms and conditions, or procedural nuance – meant that commentators had to find ways to engage wide audiences in relatively niche industry issues. The result of these drivers? Commentators leveraged archetypal figures and narratives to bring apparent “clarity” and emotional weight to the stories, and quickly. They used binary language – dark and light, dirty and clean, pure and corrupt. They identified stock characters – villains, heroes, and victims. They used formulaic narrative trajectories, with inflection moments of rising tension and conflict, realisation and climax, catharsis and resolution (whether through criminal charges or the already-accomplished public demolition of reputations and credibility). Using these pre-existing patterns that audiences could immediately recognise was easier, clearer, and more exciting. The algorithms of stories were an explanatory lens for a tangle of detail.

The Royal Commission lawyers used many of the same tactics for the same reasons – often driving and framing the resulting coverage. Lawyers, like the best politicians, know how to use the power of story. In fact, the ‘baby-faced assassin’ QC Michael Hodge wrote Clinton: The Musical , years before his Commission performance. Self-interested as it sounds, our analysis also showed a difference in reputational outcomes between those brands who ‘left it to the lawyers’ to run all aspects of their performance, and those who applied more specialist narrative expertise (such as PR advice). But the use of familiar narrative patterns also meant that for those involved it was a zero-sum game – you were a hero warrior like Rowena Orr, or you were a villain; you were either creeping around in the shadows or you were shining the torch. There were no grey areas left on the map. This, in turn, predetermined the ending for many of the characters – because we all know what happens to the wolf after he bullies the pigs, or to the evil, greedy banker who steals from the poor, the weak, and the dead.

The Royal Commission lawyers used many of the same tactics for the same reasons – often driving and framing the resulting coverage. Lawyers, like the best politicians, know how to use the power of story. In fact, the ‘baby-faced assassin’ QC Michael Hodge wrote Clinton: The Musical , years before his Commission performance. Self-interested as it sounds, our analysis also showed a difference in reputational outcomes between those brands who ‘left it to the lawyers’ to run all aspects of their performance, and those who applied more specialist narrative expertise (such as PR advice). But the use of familiar narrative patterns also meant that for those involved it was a zero-sum game – you were a hero warrior like Rowena Orr, or you were a villain; you were either creeping around in the shadows or you were shining the torch. There were no grey areas left on the map. This, in turn, predetermined the ending for many of the characters – because we all know what happens to the wolf after he bullies the pigs, or to the evil, greedy banker who steals from the poor, the weak, and the dead.