Written by: Auritro Kundu | AGF

Geopolitical tensions, global chip shortages and a focus on reshoring production capabilities all point to what we believe to be an attractive investment opportunity in Semiconductor Equipment manufacturers.

Semiconductor Capital Equipment companies – the Arms Dealers of AI

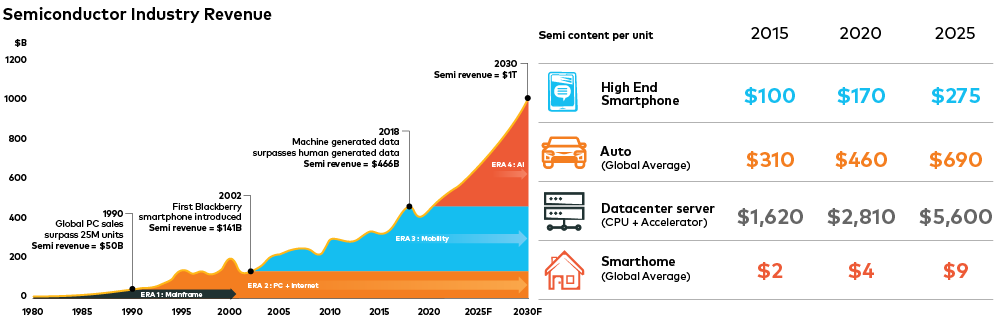

The Era of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has begun – and it has brought with it profound secular growth and innovation. Data generation in categories such as automotive, home and industrial internet-of-things (IoT), smartphones and data centers, is expected to see massive growth over the next decade. This will require faster, higher-bandwidth communications to transport the data. Revenues in the semiconductor industry are expected to reach $1 trillion (all figures expressed in U.S. dollars) by 2030 as the need for more semiconductor wafers within each of these categories continues to increase (Figure 1 – LHS).

To meet these demands, a great deal of further investment and build-out will be required, with the semiconductor capital equipment (semi cap) industry – the companies that manufacturer the equipment used to make the chips – at the heart of this. Further, we believe the semi cap industry demonstrates high barriers to entry, deep moats and business models that are hard to replicate.

Source: SEMI, VLSI, Applied Materials Analyst Day (April 2021)

Semiconductors are a capital-intensive industry, with overall capital expenditure (capex) exceeding $100 billion annually. Manufacturing equipment is the largest spend, with semiconductor water fabrication equipment (WFE) accounting for ~60% of total semiconductor capex. As the underlying semiconductor industry continues to expand, so does WFE spend. There are many steps involved in manufacturing semiconductor chips, but it can be simplified down to four major steps. Semiconductors are made by depositing materials onto the silicon wafer, patterning the wafer, removing materials from the wafer and monitoring/inspecting the process. This process is repeated over and over, mixed in with some cleaning, to complete chip circuitry.

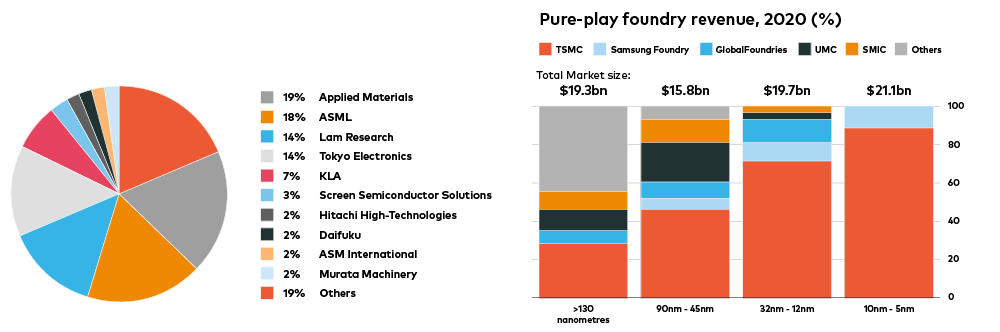

The top five semi cap companies in the world control ~70% of the WFE market (Figure 2 – LS). Their largest customers include the largest foundries in the world such as TSM, Samsung and Global Foundries (Exhibit 2 – RS), with foundries representing approximately 60% of WFE spend.

Source: LS - Gartner, Bernstein analysis (March 2021); RS - Bain/IC Insight/Gartner (March 2021)

WFE spend going higher – on a path to $100 billion annually

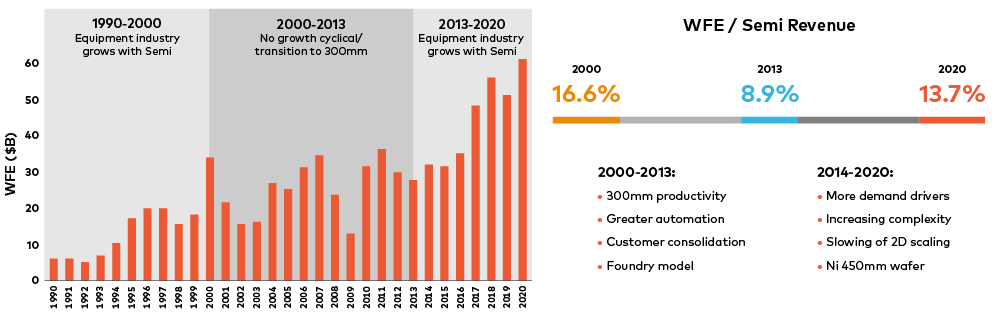

WFE spend is expected to hit $85 billion in a base case scenario and around $100 billion in a high case scenario by calendar 2024, according to Applied Materials at its 2021 Analyst Day (April 6, 2021). This compares to $70 billion in 2021, which is up from $63 billion in 2019 and $53 billion, according to data from VLSI Research (February 4, 2021).

Firstly, the industry has the benefit right now of increasing capital intensity driven by the higher complexity of the manufacturing process to add capacity at what is called the “leading” edge. Moore’s Law is often referenced in the semiconductor industry, where every year companies try to make transistors smaller with increased power performance. Semi fabs are based on the number of transistors, the smallest component of a chip, per square millimeter. The most advanced fabs right now are five nanometers (nm). Simplistically, the smaller the nanometer rating, the more transistors per square millimeter. Where the competition lies is getting to the next “leading” edge – 5 nm now, then 3 nm, and so on. TSM is currently the market leader, because of their competitive advantage in manufacturing at that leading-edge node.

Secondly, the semi cap industry is also benefitting on the cost side. Traditionally, every decade, the industry has moved to a larger wafer size, which lowered costs for the foundries but was a headwind to growth for the semi cap companies. Currently, the leading-edge wafer is 300 millimeters (mm). In the mid 1990s, that was 200 mm and in the 1980s, it was 150 mm. The wafer size itself has no impact on performance, but does impact the cost to manufacture relative to the added capacity. Looking at the history of the semiconductor industry, there was typically a 10-year period of an upward trajectory in wafer sizes, followed by digestion period where there is no increase. However, as Applied Materials points out at its analyst day (Figure 3 - RHS), the move to 300 mm, which started in the early 2000s, has stayed constant and wafer sizes are unlikely to increase to 450 nm in the near future. From 2000 to 2015, the move to a 300 mm wafer size was a negative impact to the semi cap industry, as it brought on too much capacity offered too cheaply. From 2000 to 2015, the semiconductor industry revenues grew 70% and unit volumes doubled, but WFE spend never increased beyond $32 billion for 15 years (Figure 3 – LHS). At the beginning of 300 mm, for example, it took Intel 16 weeks to build a wafer, and by 2015, production time was down to six weeks. The larger wafer size was free capacity for semiconductor manufacturers, but a headwind to growth for semi caps companies.

Source: SEMI, VLSI, Applied Materials Analyst Day (April 2021)

Semiconductor supply shortages – the need for more capacity

Much has been made in recent weeks related to semiconductor chip shortages, but it is important to recognize that the semiconductor industry has always been cyclical, with massive periods of over-supply and under-supply. Currently, companies are reporting chip shortages and extended lead times, and there are possible concerns of double ordering. Apple, for example, announced a projected ~$3-4 billion hit to revenue in its upcoming June quarter on the conference call related to decreased production of Macs and iPads due to supply constraints. BMW, Honda and Caterpillar have made similar projections. Ford now expects to lose about 50% of its planned Q2 production specifically tied to a Japanese supplier (believed to be Renesas), according to its Q1 2021 press release (April 28, 2021). All told, the company stated that the broader global semiconductor shortage may not be fully resolved until 2022 and now assumes that it will lose 10% of planned second-half 2021 production. The company expects to lose about 1.1 million units of production this year to the semiconductor shortage.

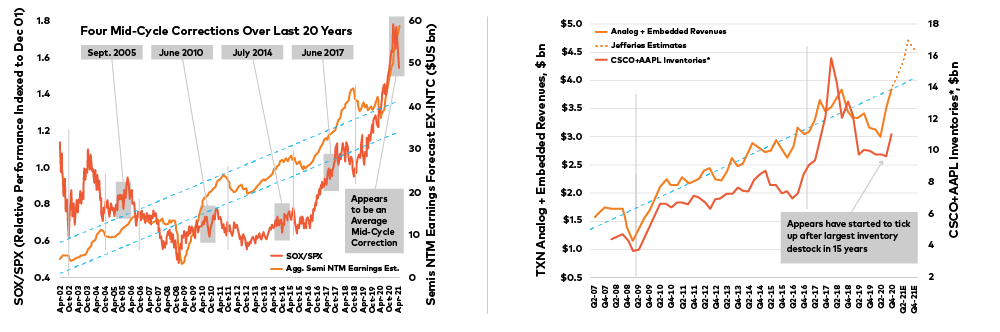

However, it is hard to call this a semiconductor industry peak when demand for chips is far outpacing supply. Each of the past four semiconductor cycles had mid-cycle corrections that on average lasted nine weeks and resulted in 1,100 basis points (bps) of underperformance for the Philadelphia Stock Exchange Semiconductor Index (SOX) versus the S&P500 Index. The range for the four mid-cycle corrections is 4-to-13 weeks in duration and 900-1,500 bps of underperformance. On average for the past four cycles, the SOX recovery between the mid-cycle correction trough and cycle peak was 2,550 bps of outperformance versus SPX over 26 weeks. We believe there remains more upside for semiconductors, based on analysis of shipments, supply chain inventories and semi lead times.

Source: Jefferies (May 2, 2021), Factset; *CSCO+AAPL include CSCO and AAPL inventories and CSCO purchase commitments

Why did this happen? What is happening now was not necessarily caused by COVID alone. Overall, the Auto vertical is about 15% of total semiconductor revenue. The semi industry was going through an industry correction in 2019, and when COVID-19 resulted in global lockdowns in early 2020, the sales of autos went down, further exacerbating what was already happening.

Today, we are further short of capacity with significant pent-up demand and high levels of savings. In general, there are three ways for supply growth to catch up to demand. The first and the easiest is when existing capacity that has been under-utilized can be maximized, usually taking 90 days (the cycle time of a wafer through a facility). The second is to de-bottleneck back-end manufacturing (takes 1-2 quarter lead times on tools there). Finally, companies can build brand new wafer capacity, which typically takes 12-24 months. With the supply chain shortage expected to last anywhere from H2 of 2022 through to 2023, the foundation is there for this semiconductor upturn to be stronger for longer.

Longer term, today’s chip shortage adds to the case for onshoring and diversifying geographic supply chains, especially for the evolving geopolitical order, as trillions of dollars of market cap and GDP are at stake.

China has semiconductor self-sufficiency goals – Made in China 2025 is real

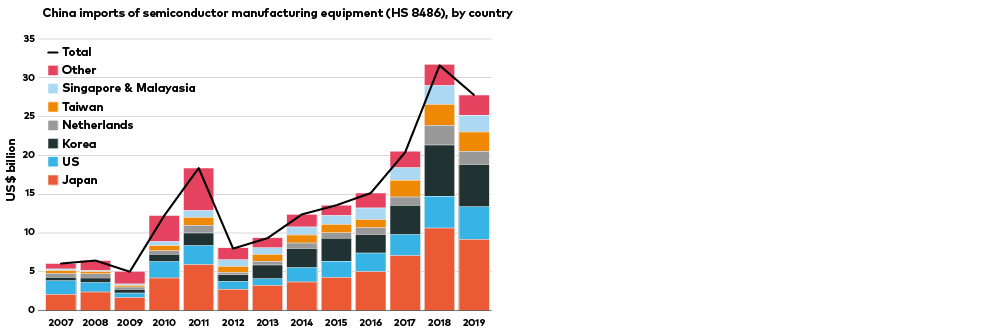

Another area for growth within the semi cap industry is China. The world’s second largest economy has set out an ambitious semi manufacturing roadmap where the plan is to reach 80% self sufficiency by 2030 . The Chinese government has directed increasing capital toward its domestic semiconductor industry as well as multinational corporations that are increasingly building facilities in the region. Friendly government policies and subsidies have helped Chinese chip makers build out their local capabilities and today close to $100 billion in funding has been dedicated to their semiconductor efforts, specifically in increased capacity. Chinese imports of semi cap equipment have also been steadily on the rise (Figure 5) despite the Trump Administration (and more recently President Biden) blocking sales of leading-edge equipment into the region, citing national security.

Source: WITS, Gavekal Dragonomics/Macrobound

U.S. Chips Act – if you build it, they will come

The U.S. share of global semiconductor fabrication stands at 12%, down from 37% in 1990, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association (September 2020), posing a real risk to U.S. companies as the global chip shortage and China’s semiconductor production ambitions put pressure on regional leaders in advanced fabrication. Being urged to revisit semiconductor supply chains, Biden’s $2.3 trillion infrastructure spending plan includes ~$50 billion for the American semiconductor industry, according to The American Jobs Plan (March 31, 2021), and is designed to advance U.S. leadership in critical technologies and upgrade America’s research infrastructure. U.S. leadership in new technologies – from artificial intelligence to biotechnology to computing – is critical to its future economic competitiveness and national security.

Specifically, the briefing states that President Biden is calling on Congress to invest $50 billion in the National Science Foundation (NSF), creating a technology directorate that will collaborate with and build on existing programs across the government. It will focus on fields like semiconductors and advanced computing, advanced communications technology, advanced energy technologies and biotechnology.

Companies are following suit. Intel recently announced its new IDM 2.0 strategy, where the company is hoping to become a major provider of foundry capacity in the U.S. and Europe to serve customers globally, with support from heavyweights including Amazon, Cisco, Ericsson, IBM, Google, Microsoft and Qualcomm. Intel will invest $20 billion to build two new wafer foundries in Arizona scheduled to begin operation in 2024. TSM and Samsung have also announced new U.S. fabrication plant investments.

What do duplicate fabs mean for the semi cap industry? The answer is that there will be longer term, higher WFE spend. In the near term, our discussions with management suggests that local production may not drive incremental demand – it just moves where the capacity is held. However, having multiple fabs spread out is inefficient and will result in duplicate spending of customer and support revenue (customer support-related revenue includes sales of customer service, spares, upgrades, etc.).

This creates another opportunity for WFE companies. Customer and support revenue is recurring in nature and profitable. For LAM Research, it represented $1.3 billion in revenues this quarter and was up 50% year-over-year, with higher margins. As Applied Materials highlighted in its Analyst Day, a greater portion of its Applied Global Services (AGS) business revenue is from recurring business. Until 2013, AGS was an after-market business, selling parts, services and legacy equipment upgrades on a transactional basis. There was plenty of low-cost competition and sub-par growth. Applied Materials pivoted to think of the business as more of a service business, helping the before, during, and after transition from R&D to high-volume manufacturing. This resulted in giving customers better outcomes during this critical transition, including accelerating time to yield, time to market, market share gains and the financial returns on multibillion-dollar investments. With AGS having moved from transactions to assurances, we believe that the recurring nature of the services businesses for Applied Materials and LAM should warrant a higher multiple in a sum-of-the-parts analysis.

Source: LS - Gartner, Bernstein analysis (March 2021); RS - Bain/IC Insight/Gartner (March 2021)

Conclusion – Dynamic Growth Prospects for a Reasonable Price

Our expectation is that the global chip supply shortage, China’s domestic ambitions and duplication of fabs globally are major geopolitical factors that should continue to increase WFE spend. From a technology perspective, WFE spend is increasing due to higher capital intensity along with no critical spending on R&D towards a larger wafer. Make no mistake, semi caps are a historically cyclical business. But we believe that with earnings revisions moving higher along with the business models becoming more recurring in nature, higher multiples are justified. At these levels, investors are getting significantly higher earnings potential at reasonable valuations for arguably the most important arms dealers in the AI era.

Related: Short-Term Chip Supply Constraints Won't Derail Long-Term Tech Trends

The commentaries contained herein are provided as a general source of information based on information available as of May 6, 2021 and should not be considered as investment advice or an offer or solicitations to buy and/or sell securities. Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in these commentaries at the time of publication however, accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Market conditions may change and the Portfolio Manager accepts no responsibility for individual investment decisions arising from the use or reliance on the information contained herein. Investors are expected to obtain professional investment advice. References to specific securities are presented to illustrate the application of our investment philosophy only and are not to be considered recommendations by AGF Investments. The specific securities identified and described in this commentary do not represent all of the securities purchased, sold or recommended for the portfolio, and it should not be assumed that investments in the securities identified were or will be profitable.

AGF Investments is a group of wholly owned subsidiaries of AGF Management Limited, a Canadian reporting issuer. The subsidiaries included in AGF Investments are AGF Investments Inc. (AGFI), AGF Investments America Inc. (AGFA)and AGF International Advisors Company Limited (AGFIA). AGFA is a registered advisor in the U.S. AGFI is registered as a portfolio manager across Canadian securities commissions. AGFIA is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland and registered with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission. The subsidiaries that form AGF Investments manage a variety of mandates comprised of equity, fixed income and balanced assets.