Written by: Bruce Aronow, CFA, James Macgregor, CFA, Samantha S. Lau, CFA and Erik Turenchalk, CFA

Smaller stocks offer diversification benefits and investment opportunities that can’t be found in their larger brethren. But because large-cap stocks have been so popular for the last 10 years, many investors have missed out on the compelling stories and advantages smaller companies can provide. Our research aims to shine some light on the universe of smaller stocks by examining their perceived risks, performance drivers and return potential—particularly amid a recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and recession. The time is right for investors to consider smaller investments that have the potential to sparkle.

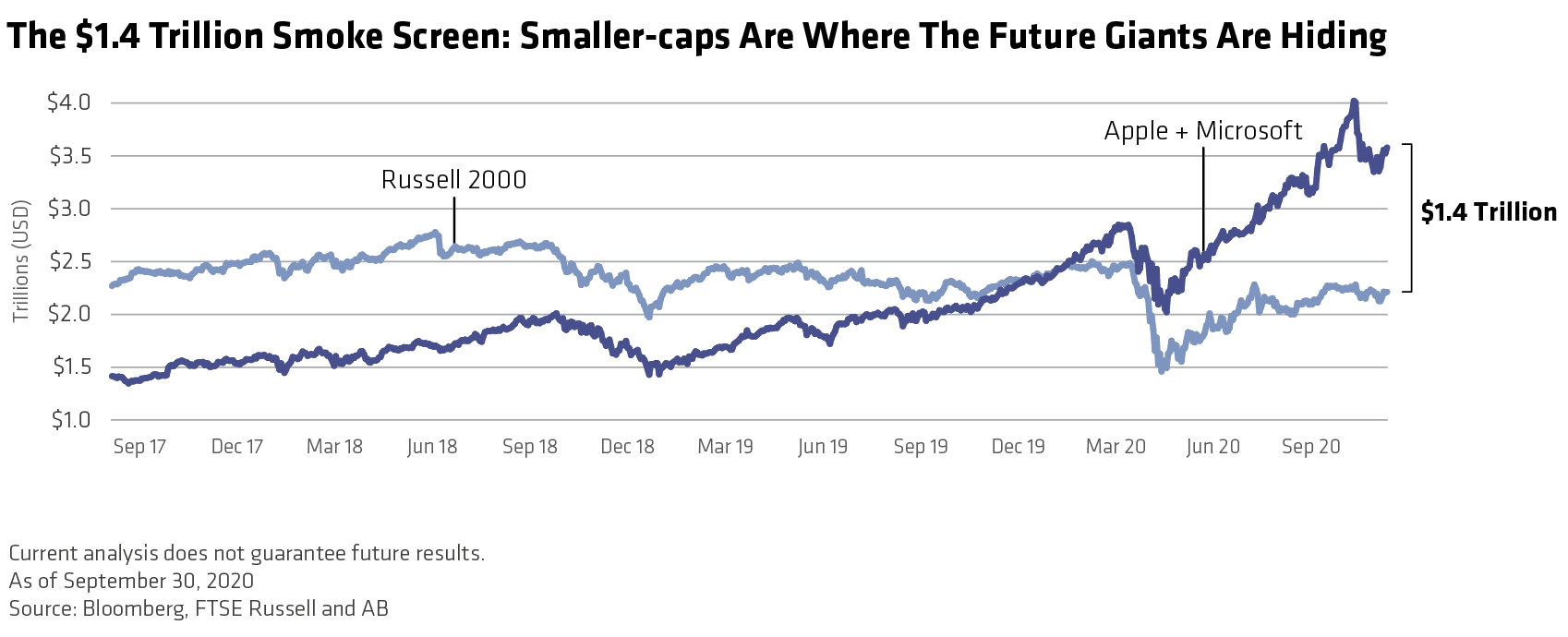

Smaller stocks seem to have gotten lost in the US market’s fascination with its giant stars. After all, when Apple and Microsoft combined are worth more than all 2,000 stocks in the small-cap index, it’s hard to see the miniature companies that look like specks of dust in the equity investing universe.

But every small company is a world in and of itself. And ignoring smaller stocks is a big mistake, in our view. Small- and SMID-cap stocks can offer investors distinct advantages, such as powerful growth drivers, innovative businesses, compelling company-level improvements and attractive valuations. What’s more, smaller companies aren’t nearly as risky as widely perceived. When carefully selected with a disciplined investing process, we believe a portfolio of smaller stocks can offer strong long-term return potential—especially in today’s environment.

What’s Behind the Small-Cap Malaise?

Performance patterns of smaller stocks can at times be difficult to explain, particularly over shorter time frames. Over the long run, however, smaller-capitalization stocks have delivered an annualized return of about 11%, outperforming their larger cohorts by at least 120 basis points a year on average. While that doesn’t sound like much of a difference, consider this: $100 invested in each of the three indices in 1926 would now be worth $2.3 million from small-cap, $1.8 million from SMID-cap and $0.7 million from large-cap.

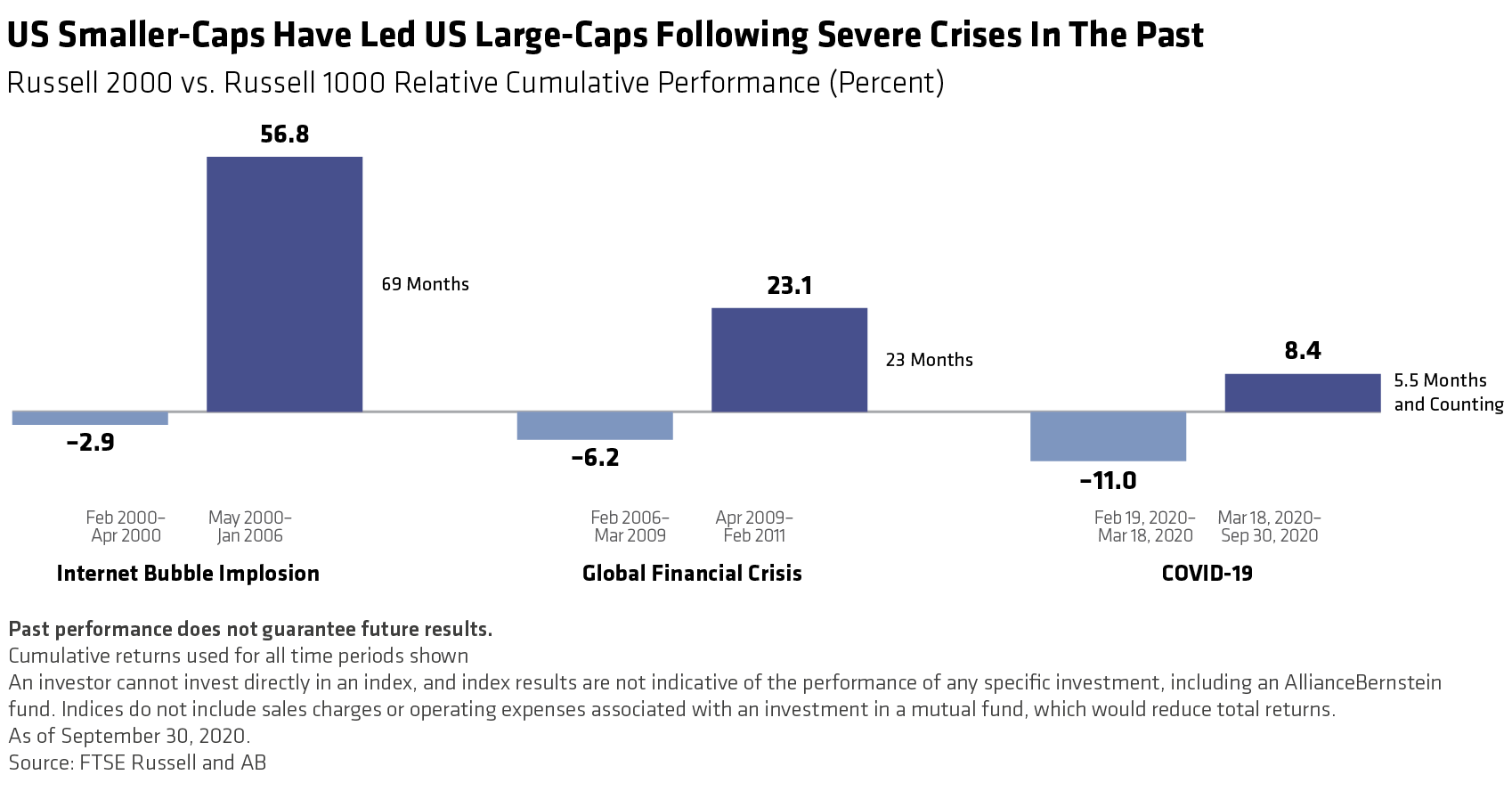

But since 2008, market currents have shifted. Investment trends have favored larger-cap stocks, at least temporarily, while investors sought safety from the below-trend economic recovery following the global financial crisis (GFC), and now the COVID-19-induced recession. During market crises, investors tend to shun smaller stocks because they’re widely perceived as riskier than their larger peers. But they also tend to rebound strongly during recoveries (Display).

Smaller-cap stock prices are more volatile than those of larger-caps, but this added volatility can create opportunity. Lower trading liquidity for small-caps can lead to inefficiencies and fundamental mispricing, especially in market crises. Trading liquidity is often a function of investor interest, and lesser-known investment stories are often overlooked in favor of larger, better-known entities such as mega-cap technology companies.

Those large-cap technology stocks have reshaped global equity markets this year, as their prices and market caps rocketed skyward. While these companies have captured investors’ attention and dollars, we believe that their rise makes the case for diversification across asset classes, such as smaller-caps, even stronger.

Smaller Stocks Make Bigger Splashes

So why have large-caps been so popular over the last decade? Governmental policies, global quantitative easing, and even the rise of passive investing, have fueled large-cap gains. Today it’s as if the laws of physics have been suspended: the largest companies keep getting larger, like trees growing to the sky.

But the laws of physics aren’t simply suggestions—they are laws. For example, the largest animals in the jungle aren’t always the mightiest. Elephants are big and strong, capable of carrying 130 humans or up to 1.5 times their body weight. But the mighty ant can carry up to 5,000 times its body weight. Which offers the better long-term return: the big lumbering elephant or the tiny but relatively stronger ant? The largest targets are also easiest to take down. As we’ve seen in previous market bubbles, some of the elephants are eventually taken out by smaller, more nimble new products and competitors that undercut older business models and products.

Some of the largest US companies have made a pretty big splash year to date. For example, Amazon, one of the five largest companies in the S&P 500, has returned an incredible 70% through September 30, 2020. And by that day, the combined market cap of just Apple and Microsoft was $1.4 trillion greater than that of the entire Russell 2000 small-cap index (Display).