After a historic market crash and a lightning rebound, active manager performance is under the microscope. But beyond returns, investors should consider many angles when evaluating active managers through an unparalleled global crisis and an indefinite period of economic uncertainty.

How did your active equity portfolio manage risk through the downturn? Did the portfolio maintain a strategic focus while adapting to the unfolding crisis? What’s the best way to position for the pandemic’s long-term effects on the global economy?

The answers to these questions require a broad understanding of what active equity portfolio managers are paid to do. Beating a benchmark is essential—but it’s only one dimension of a stock picker’s role. In our view, the COVID-19 crisis has reinforced the many functions that active managers fulfill for investors. While passive investing has its appeal as a low-cost way to access market beta, we think active strategies offer compelling advantages, especially in today’s unstable and uncertain environment. Here are 10 angles for evaluating how active managers can help investors get through today’s volatile market conditions and achieve long-term investment success.

1. Finding Winners in Crisis Markets

With the pandemic inflicting massive damage across sectors, industries and companies, passive portfolios will hold shares of many companies that are severely impaired. Active managers can identify select companies that have a much better chance of withstanding the pressure and performing well over the long term.

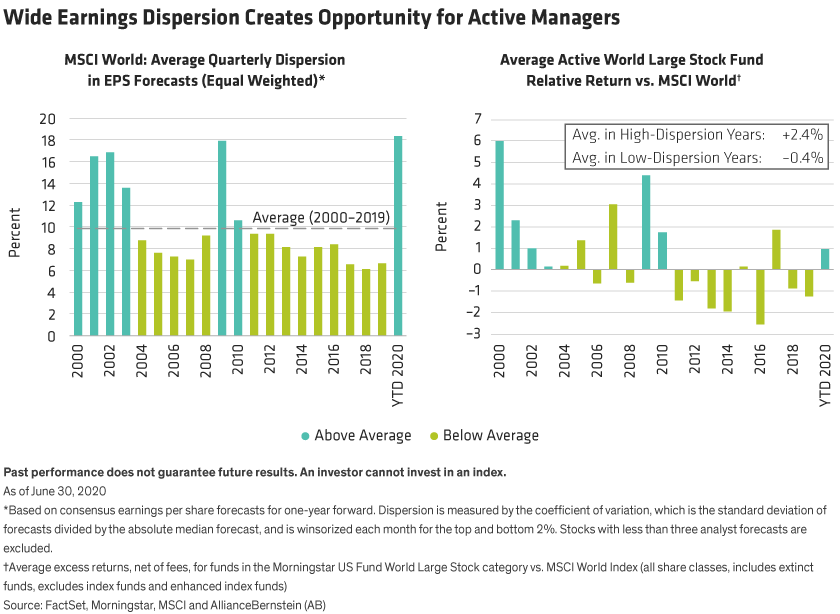

This has become harder today because COVID-19 has prompted extremely wide dispersions in various company indicators. Valuations, growth and profitability metrics are showing vast differences between top and bottom ranks. Earnings forecasts for MSCI World Index companies are now more widely dispersed than any time in the last 20 years (Display, left). Yet this dispersion creates fertile ground for active managers to sift for the most promising candidates, based on research into business models, balance sheets, industry trends and management capabilities. In the past, when earnings dispersion was wide, the average active global stock fund outperformed the MSCI World (Display, right).

2. Long-Term Performance Trends Are Better than Perceived

Active managers get a lot of negative press. But is it really deserved? Over shorter periods, active managers haven’t fared particularly well. But over 10-year periods, most active managers in several categories have beaten their benchmarks (Display). That’s important for investors with long-time horizons and can help provide context to cope with short-term stress and volatility.

What about US large caps, where performance trends have been less impressive even over longer time periods? It’s true that the highly saturated US large-cap equity space makes it harder for active managers to outperform. However, within US large-caps, certain categories of active managers—such as concentrated portfolios—have delivered much better results over time. And even across the broader US large-cap universe, we believe that investors who shop wisely, focusing on active managers with a clear investing philosophy and disciplined stock-selection and portfolio construction processes, can identify portfolios that should consistently deliver excess returns.

3. Risk Management Is More than Just a Black Box

Managing risk has become much more complicated in recent years. Investors have more technological tools to help ensure that a portfolio stays on course through volatile market spells. Since the global financial crisis, most risk models used by portfolio managers have become much more sophisticated. But they’re also backward looking, since they rely predominantly on historical data. As a result, many standard risk models struggled to cope with the unprecedented effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. These included: the sudden disruption of global supply chains; the shutdown of cities; the breakdown of formerly reliable correlations between industry sectors and investment factors; and the collapse of OPEC+*, which triggered violent reactions in energy and stock prices.

To effectively manage long-term risks, active investors can consider multiple scenarios and model cash flows to understand how companies will perform through a prolonged revenue shortfall. Big data can help identify and address cluster risks—when groups of stocks that aren’t typically similar become correlated. Diversification can be adjusted to help keep a portfolio on track, even when conventional style and factor relationships are breaking down. Combining fundamental company analysis with a holistic view of how stocks, sectors and scenarios interact in new and unexpected ways can help investors manage unprecedented portfolio risks through a historic market event.

4. Political Risk: Adapting to Exogenous Influences

We live in troubled times. Many countries are being rocked by political polarization and instability, while geopolitical tensions are simmering. The US election in November, Brexit and US-China trade tensions are all adding uncertainty to a world that’s coping with the effects of the coronavirus pandemic and recession.

Political regimes have historically had a minimal impact on the long-term trajectory for US equity markets. However, political policy can have a profound impact on sectors, industries and companies. And predicting political twists and turns is notoriously difficult. Stock pickers must be attuned to the potential of exogenous shocks such as political and regulatory decisions to affect some companies disproportionately. Active managers have the ability and flexibility to adjust holdings that have become more vulnerable to political, geopolitical and regulatory risks while leaning into stocks that may benefit from policy decisions. In contrast, passive portfolios leave investors fully exposed to sectors or companies that might get hit harder by a political outcome.

5. Avoiding Concentration Traps

Benchmarks tend to become very concentrated when certain groups of stocks are in favor. During the dot-com bubble in 1999, for example, technology stocks made up 33% of the S&P 500 Index; when the bubble burst, investors who were too heavily weighted in the sector got badly burned. Today, five of the largest US stocks comprise 22.6% of the S&P 500 and nearly 37% of the Russell 1000 Growth Index (Display). And the market value of the 100 largest US companies is now greater than all non-US developed markets (as measured by the MSCI EAFE). These distortions can unravel quickly when momentum turns.

Trends accelerated by the pandemic have fueled growth in the use of technology, which has supported the strong performance of Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet (Google’s parent) and Facebook. But history suggests that market leaders don’t stay at the top forever. Active managers can provide investors with measured exposure to some of the top names while also ensuring that a portfolio doesn’t get too heavily concentrated in frothy areas of the market that may be prone to a nasty correction.

6. Controlling Regional Exposures in Global Allocations

For global investors, market trends can skew a portfolio’s exposure to regions or countries. Because of the strong performance of the top five US growth stocks, US equities now make up more than 66% of the MSCI World versus about 30% three decades ago (Display). While there may be good reasons for investors to overweight or underweight specific countries, a passive portfolio could end up with too much weight in countries that are relatively expensive. Active managers can adjust country exposures to reflect changing opportunities in individual stocks—regardless of where they’re domiciled. This can foster a more balanced country exposure that isn’t influenced by the performance of a specific country or region.

7. Consistency and Stability in Upside/Downside Capture

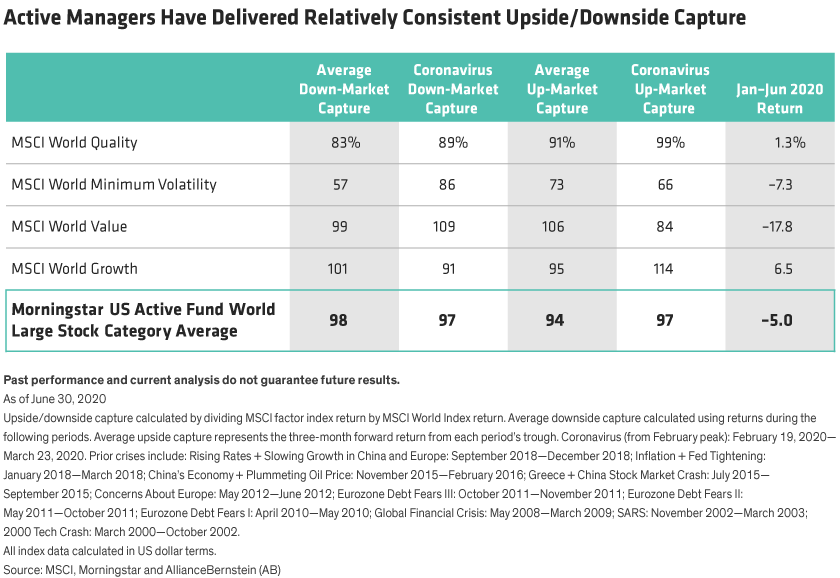

When a crisis strikes, investors want to understand how their portfolio’s strategy is likely to perform through the storm. Upside capture and downside capture is becoming an increasingly popular metric for evaluating how much of a portfolio will gain relative to a rising market, and how much it tends to fall relative to a downturn. During the coronavirus, these trends were put to the test. Our research suggests that some of the leading global factor indices did not perform in line with expectations, while the average global equity fund did deliver expected returns.

For example, the downside capture of the MSCI World Minimum Volatility Index was 86% during the COVID-19 crash in February and March of 2020, while in previous drawdowns, it captured only 57% of the market’s decline. When markets recovered in the subsequent months, the MSCI World Value’s upside capture was much lower than usual at 84%, while the MSCI World Growth’s upside capture was much higher than usual at 114% (Display).

For active global funds, the average downside capture and upside capture was similar to historical performance on the way down and up. To be sure, many funds didn’t meet expectations. However, in our view, active portfolios with a clear philosophy and structured investment process are better positioned to deliver consistent results for investors in up and down markets alike.

8. Sector ETFs May Contain Hidden Risks

Technology and healthcare stocks led global markets through 2020. So naturally, many investors seek to capture these strong performance trends in sector-specific portfolios. Yet doing so in passive sector or industry portfolios can be a risky approach, in our view.

Investing in a technology ETF will provide very heavy exposure to the largest mega-cap names. For example, the two largest ETFs in the US have more than 40% exposure to Microsoft and Apple. While these companies may offer good investment opportunities, heavy exposure to the largest names can create disproportionate risks. Many other tech companies—including small- and mid-cap stocks—also offer strong growth potential as enablers of tomorrow’s digital trends.

Passive strategies are backward looking, because in many cases, the largest weights are companies that have performed strongly in the past. As a result, they can’t really capture the innovative potential of smaller companies that might be tomorrow’s winners. Large ETFs may hold some smaller technology companies, but they aren’t able to increase exposure to smaller companies with strong future potential, and in some cases, they can’t hold smaller companies that might not meet index-inclusion requirements. For example, the largest technology ETF has more than 300 stocks, but the top 10 holdings account for more than 60% of assets. An active approach can provide more balanced exposure to the sector without getting too heavily weighted in a small number of very large stocks.

US healthcare stocks tend to be unstable during an election year. Many business models are vulnerable to policy decisions that can change dramatically depending on the outcome of the election. However, we believe investors can find opportunities in the sector in companies that are relatively immune to political noise. For example, in areas like gene sequencing, robotic surgery and the digitization of medical services, companies can be found with strong long-term business drivers. Healthcare ETFs can’t distinguish between companies that are vulnerable to political decisions and those that aren’t. Actively managed healthcare portfolios can focus on businesses that are likely to thrive over the long term no matter the outcome of an election.

9. ESG Integration: Investing Responsibly via Proactive Engagement

Increased demand for responsible investing products has led to the creation of passive portfolios based on environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings. But can you get a truly responsible investing allocation based on ESG rating alone? While ESG ratings are an important component of an RI strategy, we believe standard rating models are flawed. They can’t identify companies that are improving their ESG practices and have the right corporate culture for success. And only an active approach can include engagement with management, which is an essential ingredient for promoting positive change in corporate behavior on ESG issues that can increase shareholder value. Passive portfolios must own every stock in an index, so they cannot protest a company’s behavior by reducing positions.

Engagement with management is especially important today, when investors must assess how companies are managing a tricky balancing act between spending on employee welfare and community engagement amid the pandemic.

10. Passive Is More Active than You Think

Just a decade after passive portfolios started to take off, investors have more choices than ever before to buy passive exposure to a region, sector, factor or trend. Yet with so many passive ETFs to choose from, investors may be surprised to discover that even within the same category, they aren’t all the same. For example, there are many different methodologies to construct an ETF that focus on quality stocks. That’s why the return dispersion of 10 of the largest passive US quality ETFs that we looked at was 11.2% over a 12-month period through September 22, while the return spread between the most popular US low-volatility ETFs was 14.6% over the same period (Display). Similar trends can be seen in global and emerging-market passive portfolios.

So choosing a passive portfolio is, in fact, an active investment decision. Since the return dispersion within a passive category is often wider than the typical fee paid to an active portfolio manager within that category, we believe the cost is justified—especially considering the many additional benefits that an investor gains from paying for an active portfolio.